40 years ago, when physically absent social interactions first began to invade our lives with unseen, unheard people sending us messages, services like CompuServe’s CB supported the clamoring digital hoi polloi. The fascination of exchanging unspoken ideas with strangers, imposters and (sometimes) fools was so compelling, participants would spend hours interacting, oblivious to the ever-running connect-time charges meter.

Groups of online users would form, chat rooms were created where these users could share their thoughts and ideas with users that wanted to contribute to, debunk or annihilate the discussions. Flame-wars would break out over impossibly trivial matters ('Clara Peller was NOT Wendy’s mother in the “Where’s the Beef?” ad!’ What’s wrong with you??). I posted “Don’t drink and type!” to those belligerents which, of course, only enraged them further. By the time CompuServe CB died, these groups had all backed into their own corners and waited for the next-round conflict bell to ring. There was no external source, no online referee that defined the groups or their behaviors. Cooperation and opposition were organic functions.

I own up to my cyber-dyslexia. Every time I see or hear the phrase “social media,” my brain immediately translates it to “anti-social” media, but I’m not sure the “Anti-“ part is a result of the way the media is crafted or whether it is part of our individual identity.

Are social media algorithms truly to blame for online polarization, or do our own choices play a bigger role?

Social media algorithms collect and analyze vast amounts of user data, such as browsing history, interests, and interactions. This information is used to tailor content feeds to individual preferences, ensuring that users see posts most relevant to them. Algorithms heavily weigh engagement signals like likes, shares, comments, and watch time. Content that receives higher engagement is more likely to be promoted and shown to a wider audience. Once user data and engagement signals are collected, algorithms rank content based on predicted relevance and interest. Posts that score higher are surfaced at the top of users’ feeds, while less relevant content is shown less frequently or not at all. Ranking is continuous. Updates happen as soon as new data arrives.

Like the Wendy’s commercial back in the mid-1980s, algorithms can amplify divisive content, but that isn’t their design. They function by interaction. They are more like the force that kept the connect-time clock running in the CompuServe CB. They are engines of profit. These back-end processes do not create the groups. People follow the subjects and experiences that reinforce their own perspectives and join with the like-minded.

Understanding the human element in all of this cyber-selected content is key to understanding and abandoning algorithmic polarization. Not all engagement signals are beneficial; negative interactions, such as outrage or controversy, can also boost content visibility. Algorithms do not distinguish between positive and negative engagement, focusing instead on overall activity levels. What starts as a personal action on social media can escalate into widespread influence, affecting conversations and shaping public opinion. Recognizing this path will highlight the importance of mindful engagement online.

We are all curious, it is part of who we are. When we click around on the internet looking for some tidbit of information —“Was Clara Peller really a vegetarian?” [No - Following her, popularity, she was presented with a 25-pound hamburger by the cattle industry and was gifted an apron that read "Beef Gives Strength”.] And while a search like that may spawn hamburgers ads all over your chosen media, be aware that the engine that sends the content back to us is not trying to raise your cholesterol or shorten your lifespan or drive you to some nutrition-oriented political party. It is only there to make money by offering you what you have already looked for.

If you are careful selecting how content is accessed, you can change the choices presented by the algorithms. If you use a browser like DuckDuckGo to access content instead of proprietary apps, your tracks are more difficult to follow. And if you want to see a sudden and startling change in the content that is offered to you, open a browser and type Happiness in the Search bar, you may be surprised at what begins to follow you around.

That result is not in their algorithm, but in ourselves.

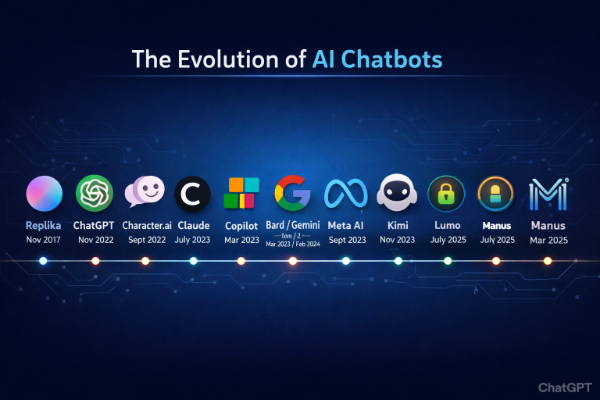

New AI seems to appear every month. I decided to dig into the history of hem in order to crate a brief chronology that focuses on publicly accessible chatbots (not internal research models or early limited-access releases. Many other AI assistants (e.g., Ernie Bot in China, Perplexity AI, Amazon Alexa+ web chatbot) have also become available in various regions and forms, especially by 2024–2026, but specific launch dates vary by market and rollout strategy.

New AI seems to appear every month. I decided to dig into the history of hem in order to crate a brief chronology that focuses on publicly accessible chatbots (not internal research models or early limited-access releases. Many other AI assistants (e.g., Ernie Bot in China, Perplexity AI, Amazon Alexa+ web chatbot) have also become available in various regions and forms, especially by 2024–2026, but specific launch dates vary by market and rollout strategy.