Yet More AI: Manus

Manus is a newer AI from Meta. Before the acquisition of Manus, Meta’s primary AI system was Meta AI, powered by the Llama (Large Language Model Meta AI) series of models. While Meta AI was a robust "chatbot," Manus represents a shift toward "agentic AI."

Why did they make the move? Meta AI was integrated across WhatsApp, Instagram, and Messenger. It was designed to do several things: answer questions, provide information, generate images, compose text, and summarize long conversations or documents. Pretty much what every other AI chatbot was doing.

Meta AI was primarily a "conversation layer." If you asked it to "book a flight" or "build a website," it could give you advice or write code, but it couldn't actually go into a browser, navigate a website, or complete the transaction for you.

In late 2025, Meta acquired the Singapore-based startup Manus for a reported $2 billion to solve the "execution gap" between talking and doing.

So while you would ask a chatbot to "Write a travel itinerary for a road trip from San Diego to San Francisco," you could ask an agentic AI to also "Book the hotels for this itinerary."

So while you would ask a chatbot to "Write a travel itinerary for a road trip from San Diego to San Francisco," you could ask an agentic AI to also "Book the hotels for this itinerary."

Manus can plan and execute multi-step tasks. It can open a virtual browser, research a topic, create a spreadsheet, and then email that spreadsheet to a colleague without human intervention. Competitors like OpenAI (with Operator) and Google (with Gemini Agents) were moving toward AI that can control a computer. Meta needed Manus's "execution layer" to stay competitive.

Where's the money? Meta is integrating Manus into its Ads Manager and business tools. This allows businesses to automate complex marketing workflows—like building entire landing pages and running ad reports—simply by asking.

More history:

September 2023: Meta AI first debuted publicly, initially on devices like smart glasses.

April 2024: Wider rollout across Meta’s social apps.

April 29, 2025: Standalone Meta AI app released.

March 6, 2025: The autonomous AI agent Manus was officially released to the public. It gained attention as an early example of an autonomous AI agent that could operate without continuous human guidance, and in late 2025, it was acquired by Meta.

Manus is an example of what’s often called an “agentic” AI system. Rather than simply responding to prompts, it is built to take a high-level goal and carry out the steps needed to achieve it. That might include researching information, planning a workflow, writing and executing code, analyzing data, and producing a finished output. In other words, Manus is structured to complete multi-step tasks with a high degree of autonomy. It functions more like a digital project manager or operator than a chatbot.

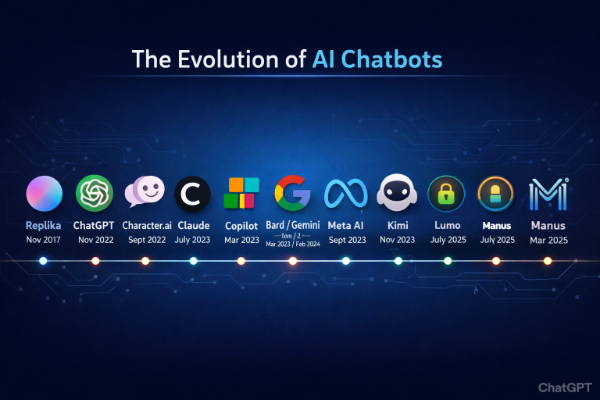

New AI seems to appear every month. I decided to dig into the history of hem in order to crate a brief chronology that focuses on publicly accessible chatbots (not internal research models or early limited-access releases. Many other AI assistants (e.g., Ernie Bot in China, Perplexity AI, Amazon Alexa+ web chatbot) have also become available in various regions and forms, especially by 2024–2026, but specific launch dates vary by market and rollout strategy.

New AI seems to appear every month. I decided to dig into the history of hem in order to crate a brief chronology that focuses on publicly accessible chatbots (not internal research models or early limited-access releases. Many other AI assistants (e.g., Ernie Bot in China, Perplexity AI, Amazon Alexa+ web chatbot) have also become available in various regions and forms, especially by 2024–2026, but specific launch dates vary by market and rollout strategy.