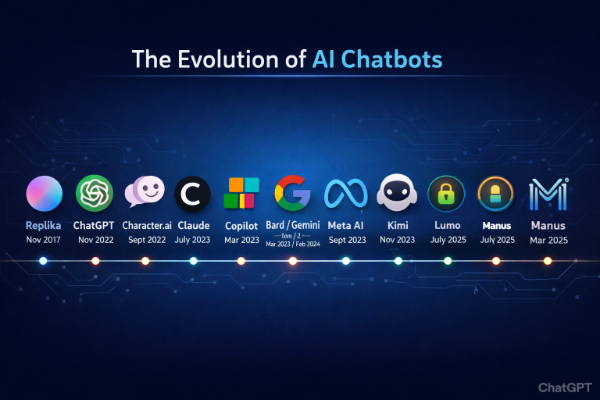

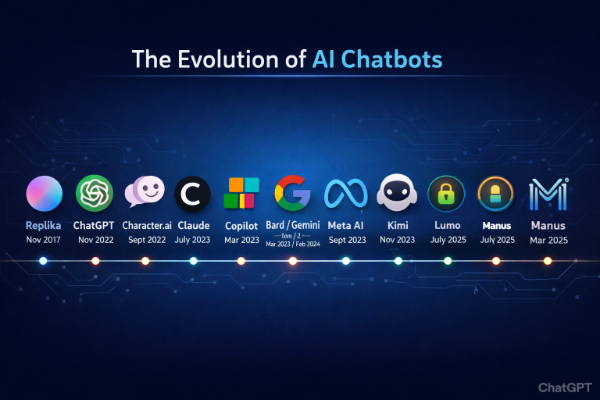

New AI seems to appear every month. I decided to dig into the history of hem in order to crate a brief chronology that focuses on publicly accessible chatbots (not internal research models or early limited-access releases. Many other AI assistants (e.g., Ernie Bot in China, Perplexity AI, Amazon Alexa+ web chatbot) have also become available in various regions and forms, especially by 2024–2026, but specific launch dates vary by market and rollout strategy.

New AI seems to appear every month. I decided to dig into the history of hem in order to crate a brief chronology that focuses on publicly accessible chatbots (not internal research models or early limited-access releases. Many other AI assistants (e.g., Ernie Bot in China, Perplexity AI, Amazon Alexa+ web chatbot) have also become available in various regions and forms, especially by 2024–2026, but specific launch dates vary by market and rollout strategy.

Some chatbots have evolved over time (e.g., Bard became Google Gemini), so “release” reflects the first broad availability to general users.

Here’s a brief chronology of major AI chatbots that became available to the public, listed in order of their public release or general availability (primarily focused on the modern generative AI era):

Replika – Launched in November 2017, one of the earliest modern AI chatbots designed as a conversational companion.

ChatGPT – Released by OpenAI on November 30, 2022, and widely recognized as the breakthrough generative AI chatbot that sparked mainstream interest in conversational AI.

Character.ai – First beta made public on September 16, 2022, letting users chat with or create character-based bots; significant growth followed into 2023.

Anthropic’s Claude (public) – First broadly available version of the Claude AI chatbot launched in July 2023, after initial private releases earlier that year.

Google Bard – Announced and publicly launched in March 2023 as Google’s first consumer AI chatbot; later rebranded under the Gemini name.

Microsoft Copilot - Public Release: March 7, 2023 - Microsoft Copilot was launched as a generative AI chatbot and assistant, integrated across things like Microsoft 365 (Word, Excel, Outlook), Windows, and Bing/Edge. In the broader AI chatbot timeline, Copilot was one of the first major assistants launched by a major tech company after ChatGPT’s debut in late 2022.

Kimi – The first version became publicly available on November 16, 2023, offering ultra-long-context interactions.

Meta AI – Launched in September 2023 within Meta platforms (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp) as an AI assistant; expanded afterward.

Google Gemini (rebrand/evolution) – In February 2024, Google rebranded Bard as Gemini and deepened its rollout as the successor to Bard with broader capabilities.

Lumo (Proton) – Launched on July 23, 2025 as a privacy-focused AI chatbot emphasizing encrypted interactions and no data training logging.

Manus Public Launch: March 6, 2025 — The autonomous AI agent Manus was officially released to the public by Meta as a general-purpose AI agent capable of planning and executing tasks independently.

So while you would ask a chatbot to "Write a travel itinerary for a road trip from San Diego to San Francisco," you could ask an agentic AI to also "Book the hotels for this itinerary."

So while you would ask a chatbot to "Write a travel itinerary for a road trip from San Diego to San Francisco," you could ask an agentic AI to also "Book the hotels for this itinerary." New AI seems to appear every month. I decided to dig into the history of hem in order to crate a brief chronology that focuses on publicly accessible chatbots (not internal research models or early limited-access releases. Many other AI assistants (e.g., Ernie Bot in China, Perplexity AI, Amazon Alexa+ web chatbot) have also become available in various regions and forms, especially by 2024–2026, but specific launch dates vary by market and rollout strategy.

New AI seems to appear every month. I decided to dig into the history of hem in order to crate a brief chronology that focuses on publicly accessible chatbots (not internal research models or early limited-access releases. Many other AI assistants (e.g., Ernie Bot in China, Perplexity AI, Amazon Alexa+ web chatbot) have also become available in various regions and forms, especially by 2024–2026, but specific launch dates vary by market and rollout strategy.