The Wayback Machine

The Wayback Machine (part of https://web.archive.org) has been making backups of the World Wide Web since 1996. Mark Graham, its director, describes it as "a time machine for the web." It does that by scanning hundreds of millions of webpages every day and storing them on their servers. To date, there are nearly 900 billion web pages backed up. Computer scientist Brewster Kahle says "The average life of a webpage is a hundred days before it's changed or deleted."

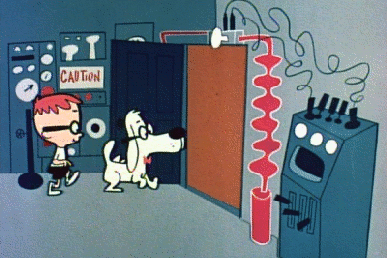

The first time I heard the name "Wayback Machine" I immediately thought of the fictional time-traveling device used by Mister Peabody (a dog) and Sherman (a boy) in the animated cartoon The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends. In one of the show's segments, "Peabody's Improbable History", the characters used the machine to witness, participate in, and often alter famous historical events.

Sherman and Peabody

It has been many years since I watched these cartoons, but I recall them as funny and educational. I might be wrong about the latter observation.

I visited the website today and searched this blog's URL https://www.serendipity35.net and found that our site has been saved 153 times between February 8, 2009, and May 3, 2024. However, this blog started in February 2006, but that was when it was a little project in blogging I started with Tim Kellers when we were working at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. At that time it was hosted on NJIT's servers, so our URL was http://dl1.njit.edu/serendipity, for which there is no record. Perhaps, the university did not allows the Wayback Machine to crawl our servers.

According to Wikipedi's entry, The Wayback Machine's software has been developed to "crawl" the Web and download all publicly accessible information and data files on webpages, the Gopher hierarchy, the Netnews (Usenet) bulletin board system, and downloadable software. The information collected by these "crawlers" does not include all the information available on the Internet, since much of the data is restricted by the publisher or stored in databases that are not accessible. To overcome inconsistencies in partially cached websites, Archive-It.org was developed in 2005 by the Internet Archive as a means of allowing institutions and content creators to voluntarily harvest and preserve collections of digital content, and create digital archives.

Crawls are contributed from various sources, some imported from third parties and others generated internally by the Archive. For example, crawls are contributed by the Sloan Foundation and Alexa, crawls run by Internet Archive on behalf of NARA and the Internet Memory Foundation, that mirror Common Crawl.

A screenshot from the blog from a decade ago (2014).

Searching on another website of mine - Poets Online - I find pages from 2003 when it was hosted on the free hosting platform Geocities. There are broken lonks and missing images but they give a taste of what the site was back then in the days before customizable CSS and templated websites. They have archived a page from March of this year and most of the links and some images come through.

The online Wayback Machine is not the one that sparked by time-traveling imagination as a child. Yes, I wanted to accompany Sherman and Mr. Peabody, but I will have to be content to the time travel of looking at things from my past on and offline.

Screen shot from DVD of Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoons., Fair use, Link

Tay was a chatbot originally released by Microsoft Corporation as a Twitter bot on March 23, 2016. It "has had a great influence on how Microsoft is approaching AI," according to Satya Nadella, the CEO of Microsoft.

Tay was a chatbot originally released by Microsoft Corporation as a Twitter bot on March 23, 2016. It "has had a great influence on how Microsoft is approaching AI," according to Satya Nadella, the CEO of Microsoft.