Open Everything 2017

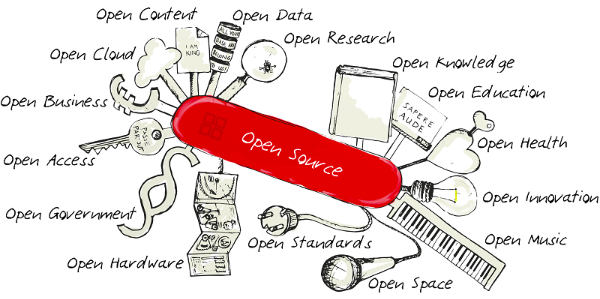

Back in 2008, I first posted here about what I was calling "Open Everything." That was my umbrella term for the many things I was encountering in and out of the education world that seemed relevant to "Open" activities based on Open Source principles. The growth I saw nine years ago continues.

I had made a list of "Open + ______" topics I was encountering then, and I have updated that list here:

access

business

configuration

hosts

cloud

content

courseware

data

design

education

educational resources (OER)

format

government

hardware

implementation

innovation

knowledge

learning

music

research

science

source as a service

source licenses

source religion

source software

space

standards

textbooks

thinking

All these areas overlap with other categories that I write about on Serendipity35.

David Wiley makes the point in talking about one of these uses -"open pedagogy" - that "because 'open is good' in the popular narrative, there’s apparently a temptation to characterize good educational practice as open educational practice. But that’s not what open means. As I’ve argued many times, the difference between free and open is that open is “free plus.” Free plus what? Free plus the 5R permissions." Those five permissions are Retain, Reuse, Revise, Remix and Redistribute. Many free online resources do not embrace those five permissions.

A colleague sent me a link to a new book, Open: The Philosophy and Practices that are Revolutionizing Education and Science. The book also crosses many topics related to "open": affordable education, transparent science, accessible scholarship, open science, and courses that share this philosophy.

That last area interests me again of late as I am taking on some work on developing courses using OER materials for this fall at a community college. These courses are not what could be labeled as "open courses." They are using Open Educational Resources. They are regular Gen-Ed courses with the traditional tuition and registration structure.

So, why remake a course using OER?

Always on the list of reasons to lower the cost for students by eliminating (or greatly lowering the price of) a textbook and using open textbooks and resources. But there are more benefits to OER than "free stuff." This course redesign is also an opportunity to free faculty from the constraints of a textbook-driven curriculum. (Though, admittedly many faculty cling to that kind of curriculum design.)

David Wiley's warning is one to consider when selecting OER. Is a text "open" if it does not allow the 5R permissions? Wiley would say No, but many educators have relaxed their own definition of open to the point that anything freely available online is "open." It is not.

For example, many educators use videos online on YouTube, Vimeo or other repositories. They are free. You can reuse them. You can usually redistribute (share) them via links or embed code into your own course, blog or website. But can you revise or remix them? That is unlikely. I fact, they may very well be copyrighted and attempting to remix or revise them is breaking the law.

You might enroll in a MOOC in order to see how others teach a course that you also teach. It is a useful professional development activity for teachers. But it is likely not the case that you have the right to copy those mate rails and use them in your own courses. And a course on edX, Coursera or another MOOC provider is certainly not open to you retain, reusing, revising, remixing or redistributing the course itself.

There are exceptions. MIT's Open Courseware was one of the original projects to offer free course materials. They are not MOOCs as we know them today, but they can be a "course for independent learners." They are resources and you were given permissions (with some restrictions; see their mission video) to use them for your own courses.

I didn't get a chance to fully participate in the OpenLearning ’17 MOOC that started in January and runs into May 2017. It is connectivist and probably seems like an "Old School MOOC" in this 2017 dominated by the Courseras of the MOOC world. It is using Twitter chats, AMA, and Hangouts. You can get into the archives and check out the many resources. It is a MOOC in which, unlike many courses that go by that label today, where the "O" for "Open" in the acronym is true. Too many MOOCs are really only MOCs.

The MOOC - massive and online and sometimes open - has been around long enough that there is now massive data collected about these courses and their participants. And yet, there is not much agreement about what it all means for changing education online or offline.

The MOOC - massive and online and sometimes open - has been around long enough that there is now massive data collected about these courses and their participants. And yet, there is not much agreement about what it all means for changing education online or offline.