Of Course, There Is Life After College

A new book, There Is Life After College by Jeff Selingo, is out this month. It looks at stories of 20-somethings and their experiences in and out of school and how those experiences shaped their success in the job market.

He looks at factors such as the skills that proved most helpful, in an attempt to discover why some students prosper, while others fail. (There is a free preview of the book's introduction.)

Jeff Selingo previously wrote College (Un)bound and there is some crossover, such as the need for students to understand the jobs (especially ones that did not exist a few years ago) available to them and the need to be lifelong learners.

There Is Life After College is about after college and the concerns about that time come not only from students but from parents. Parent are anxious about their college-educated child to successfully landing a good job after graduation and their own or the student's significant debt which (especially in an uncertain job market) may leave that child financially dependent on their parents for years to come. Both parties may well ask, "What did I pay all that money for?"

While Selingo's earlier book may have answered that question with thoughts about alternatives to the degree, such as MOOCs or competency-based degrees, this new book looks a lot at that Return on Investment (ROI).

Does where you go to college matter? Most of the data says it does. The better schools get more students to graduation on time and their name recognition value is real. My one son is in finance and for many of the Wall Street banks and firms he interviewed with they only wanted to look at Ivy League graduates. There is a nice interactive visualization tool from Jon Boeckenstedt that shows graduation rates by the selectivity of the school. The ability of the nation's oldest and wealthiest colleges to graduate white men who end up wealthy is real. Not that less selective schools mean no chance of success, but it may come with more effort required. But the really surprising take on this kind of data to me was that it's not that you should choose a college because of its graduation rate, but that the college will select you based on your propensity to graduate.

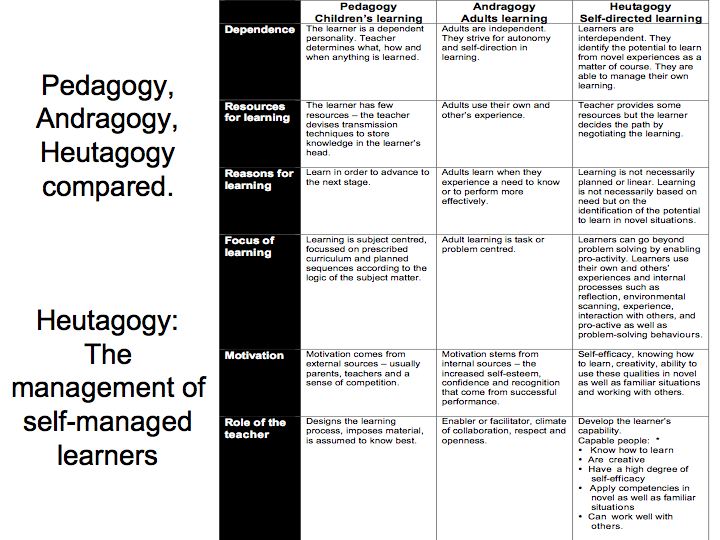

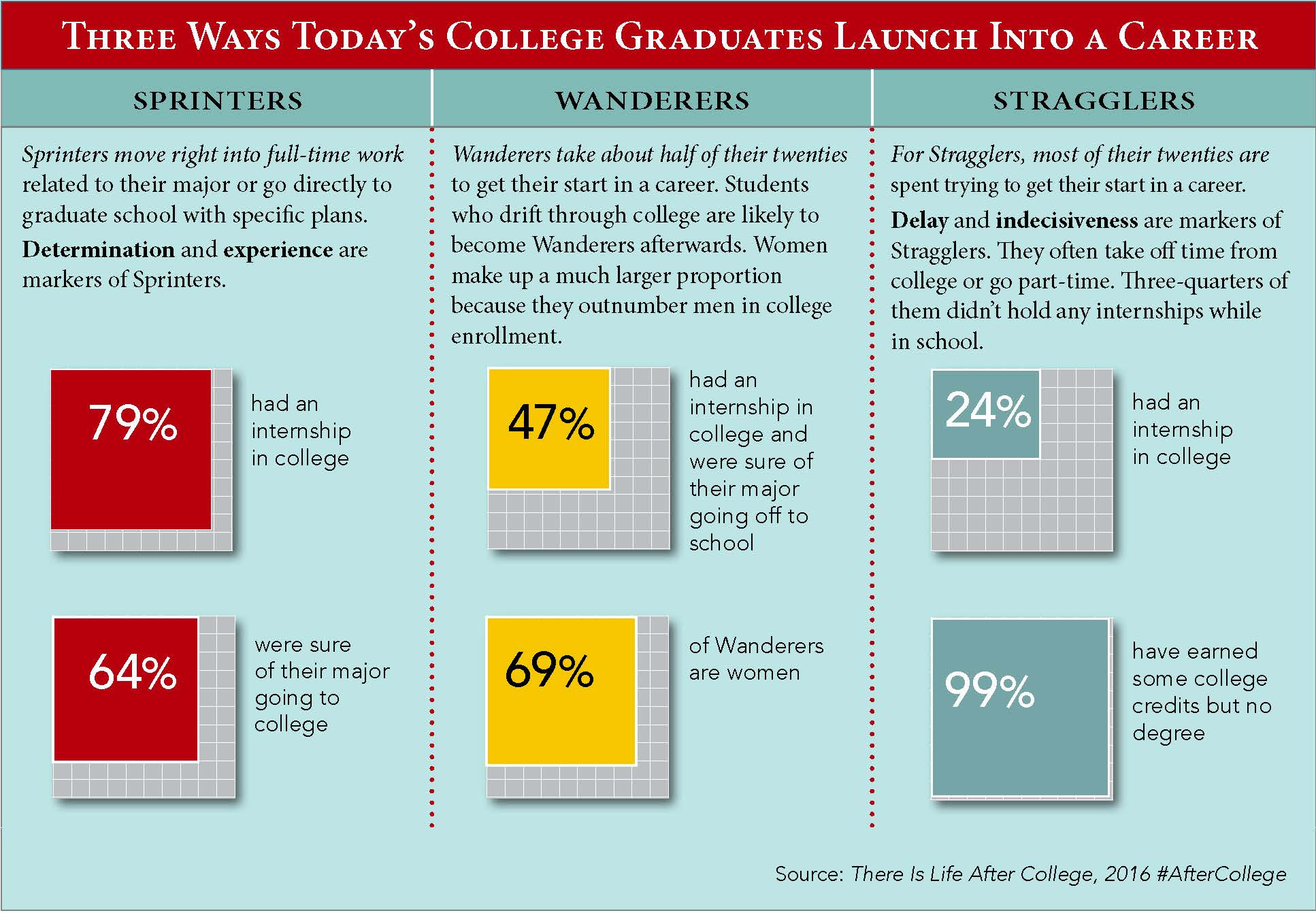

For the book, Selingo conducted a survey of young adults who had at least some college experience and were born between 1988 and 1991, giving them some time to start a career in their mid-twenties. Based on that survey, they divided the transition from adolescence into adulthood by new college graduates into three groups: Sprinters, Wanderers, or Stragglers. This charts appears in his newsletter.

The full results of the survey are in the book, but one result was that two-thirds of new college graduates fail to find meaningful employment in the years after they leave school. They either drift from job to job, live with their parents or work part-time gigs that don’t require a college degree.

Of course, there IS life after college, but the book taps a trend we see of more difficult and longer transitions to post-college life and looks to suggest ways that graduates can market themselves. He suggests that process to plan for a young professional starts at the end of high school through college graduation. Seems like this book would make a good high school graduation gift.

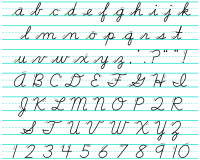

I had a conversation with a friend this past week about kids and handwriting. She was upset that her grandchild doesn't seem to be able to write or read cursive. She sees this as a big mistake. In fact, the dreaded Common Core standards call for teaching legible writing, but only in kindergarten and first grade. After that, it is all about the keyboard. Even without those guidelines, handwriting has certainly been pushed out of the elementary curriculum.

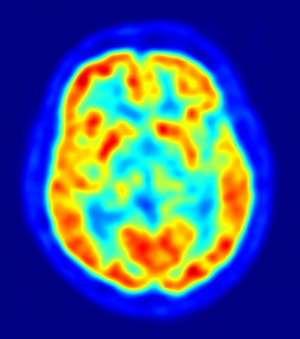

I had a conversation with a friend this past week about kids and handwriting. She was upset that her grandchild doesn't seem to be able to write or read cursive. She sees this as a big mistake. In fact, the dreaded Common Core standards call for teaching legible writing, but only in kindergarten and first grade. After that, it is all about the keyboard. Even without those guidelines, handwriting has certainly been pushed out of the elementary curriculum. New research seems to indicate that beyond what we write how we write matters. If children had drawn a letter freehand, they showed increased activity when their brain was scanned in three areas of the brain that are activated in adults when they read and write. In order to be able to read, you need to be able recognize each possible iteration of a letter no matter how we see it written - on a book's page, on a screen in different fonts or written by hand on a piece of paper.

New research seems to indicate that beyond what we write how we write matters. If children had drawn a letter freehand, they showed increased activity when their brain was scanned in three areas of the brain that are activated in adults when they read and write. In order to be able to read, you need to be able recognize each possible iteration of a letter no matter how we see it written - on a book's page, on a screen in different fonts or written by hand on a piece of paper.