Instructors, especially those who do not teach writing as a subject, often struggle when it comes to making suggestions to students about what they need to do to improve their writing. I saw a survey done by Turnitin.com of 2400 students in bachelor or graduate programs that asked what types of feedback they felt were most effective and what types of feedback they received most regularly.

Instructors, especially those who do not teach writing as a subject, often struggle when it comes to making suggestions to students about what they need to do to improve their writing. I saw a survey done by Turnitin.com of 2400 students in bachelor or graduate programs that asked what types of feedback they felt were most effective and what types of feedback they received most regularly.

The results can either be seen as encouraging or inconclusive. All types of feedback were seen by over half of the students as being either very or extremely effective. Even the lowest response, for general praise or encouragement, got a 56% positive response.

The responses to the types of feedback were more interesting. 68% said that they received general comments regularly while only 36% said they received examples regularly. Suggestions for improvement, the type of feedback rated most effective by students, was only seen regularly by 58% of students.

It is also interesting that across every category students rated feedback as being more effective than educators rated it. That lack of belief in feedback is certainly connected to the students in the majority saying that they didn’t regularly receive any feedback at all.

So the concern here for teachers is not as much what type of feedback they give, but whether they are giving enough feedback.

During the years that I directed a writing program, it was made clear to me that, just like teachers in all the lower grades, professors dreaded having to decide and deal with writing that you believe it is plagiarized. Of course, that is why Turnitin.com has become a successful company.They suggested in a blog post a very unusual approach to teaching about plagiarism. Have students copy. Intentionally.

Mimesis refers to the ability to copy. Mimicry is the practice of imitating. We often encourage students to mimic as a way of learning. We discourage students from copying. We should make the distinction clear to students.

I spent a few years on an academic integrity committee at a university. One of the most sensitive issues that came up in those meetings was about the perceived cultural differences when it came to imitating or copying by students.

The university has large numbers of international students, most in STEM fields, and many of them have their greatest academic difficulties with academic writing. The Turnitin.com post says that "To many educators, there’s a belief that students in eastern countries learn through rote memorization and copying while those in western countries focus more or original work and creative thought. Though the stereotype is obviously not the complete truth, there are cultural differences between educational approaches in countries with an eastern cultural background and those with a western approach."

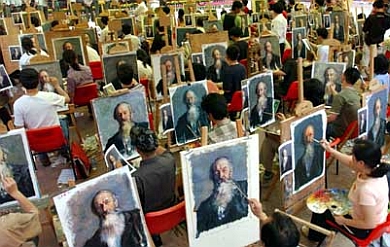

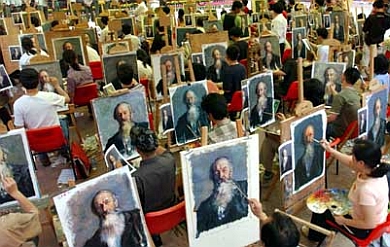

They point to research by Anita Lundberg who teaches for Australia's James Cook University at a satellite school in Singapore. Lundberg, a cultural anthropologist studying ethnography, the study of customs and cultures, says that the biggest lesson learned is that copying and imitation is a key part of the learning experience in all cultures and in nearly all areas. Mimesis can be found in all fields including writing and art, where great masters often start mimicking the works of those who came before.

With writing, it is a good idea to give students model papers for the students to work from and even mimic. Separate mimesis from plagiarism. Teach referencing and citation skills.

Jane Hart created the Centre for Learning and Performance Technologies (

Jane Hart created the Centre for Learning and Performance Technologies ( Instructors, especially those who do not teach writing as a subject, often struggle when it comes to making suggestions to students about what they need to do to improve their writing. I saw a

Instructors, especially those who do not teach writing as a subject, often struggle when it comes to making suggestions to students about what they need to do to improve their writing. I saw a