Standardized Testing for College Admissions

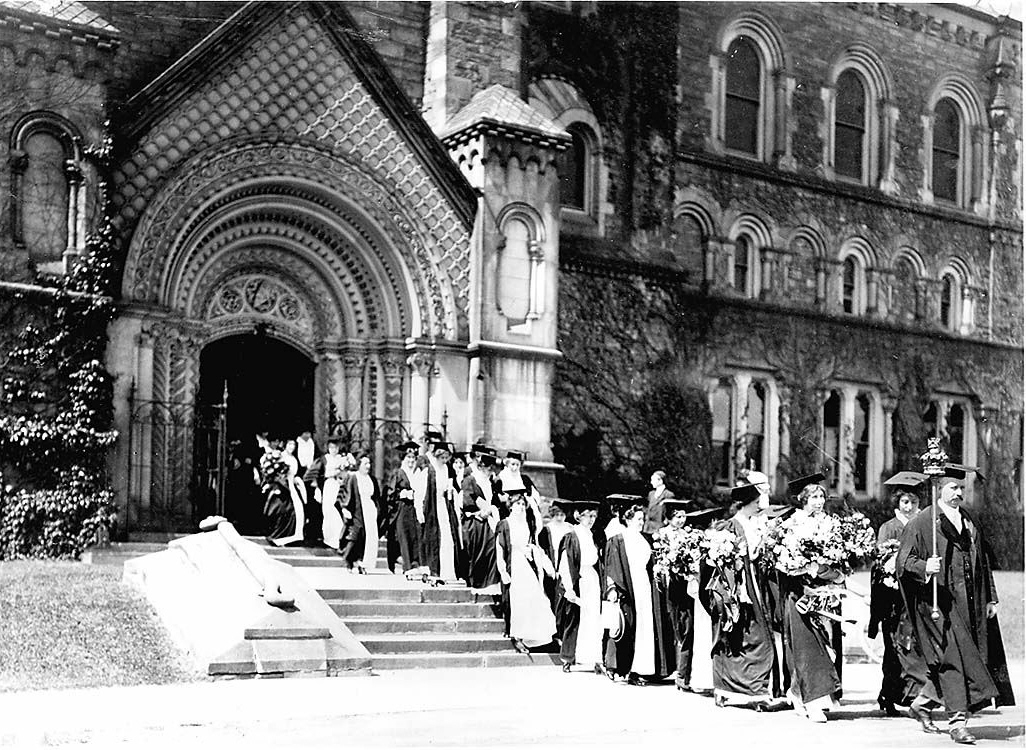

Standardized testing for college admissions is now more than 100 years old. In 1901, the first standardized tests were administered by the College Board for college admissions.

Standardized testing for college admissions is now more than 100 years old. In 1901, the first standardized tests were administered by the College Board for college admissions.

At that time, many universities had their own entrance exams, some requiring prospective students to come to campus for a week or more to take exams.

But different colleges meant different standards. Students needed to know what schools they were going to apply to in order to know what would be required. Some high schools offered separate instruction for students based on which colleges (or type of school) they hoped to attend.

Colleges on the other end might consider in admissions how well previous graduates of a particular high school had done, or might send faculty to visit high schools and rate them.

Most of us today are familiar with the SAT which we took for college admission, but that is 25 years further in the history until we arrive at that test.

From 1885 to 1900, groups including the National Education Association formed committees, discussed and argued and finally formed the College Board (initially as the College Entrance Examination Board) in the hope of standardizing curricula at high schools with a goal of making a college education accessible to a wider pool of applicants.

This may sound somewhat familiar to more modern efforts at standards, such as the current Common Core State Standards, including the standardized testing. Those first standardized college entrance exams (given to less than 1000 students) tested English, French, German, Latin, Greek, history, mathematics, chemistry, and physics.

They were essay tests, not multiple choice. They were read and scored by a team of experts in each subject. That first year, the readers sat at tables in the library of Columbia University. the grades were: Excellent, Good, Doubtful, Poor, or Very Poor. They were used for several decades but did not have wide acceptance.

We would classify those tests as achievement tests because they tested for students' proficiency in a subject. The College Board would next move to using aptitude tests meant to measure intelligence, though achievement test in specific subjects were still to be used for admissions testing.

I was surprised to read that the motivation to change was twofold. Since some high schools didn't teach some subjects (like ancient Greek) or prepare students specifically for college, an aptitude test should make the test more accessible for those students. But a much more surprising and less well known part of the history of the S.A.T. is that some proponents of aptitude/intelligence testing were college officials who were concerned about the rapid influx of immigrants being added to their student body.

A Columbia University dean worried that the high numbers of recent immigrants and their children would make the school "socially uninviting to students who come from homes of refinement," and its president described the 1917 freshman class as "depressing in the extreme," lamenting the absence of "boys of old American stock." These college officials believed that immigrants had less innate intelligence than old-blooded Americans, and hoped that they would score lower on aptitude tests, which would give the schools an excuse to admit fewer of them.

It was a small group of men who drove the use of standardized testing in America. In 1925, the College Board began to use a new, multiple-choice test. It was designed by a Princeton psychology professor named Carl Brigham. He modeled it on his work with Army intelligence tests.

This new test was known as the Scholastic Aptitude Test or simply the SAT and it was first offered in 1926. Currently, more than 1.6 million students take the SAT each year.

Students started taking a new SAT in March 2016. Most students in the class of 2017 and beyond will take the new SAT in the spring of 11th grade and again in the fall of 12th grade.

As I wrote earlier, students are already prepping for the new test, including prep online offered free by Khan Academy.

Comments. We don't have them turned on here at Serendipity35 any more. We were pounded over and over with spammers and so

Comments. We don't have them turned on here at Serendipity35 any more. We were pounded over and over with spammers and so  At the time we were running

At the time we were running  which was a very funny series of sketches. It was Saturday Night Live on the radio (with some of the same people, like Bill Murray). It was created, produced and written by staff from National Lampoon magazine and it lasted for a little over a year back in 1973 and 1974.

which was a very funny series of sketches. It was Saturday Night Live on the radio (with some of the same people, like Bill Murray). It was created, produced and written by staff from National Lampoon magazine and it lasted for a little over a year back in 1973 and 1974.