Return to the One-Room School

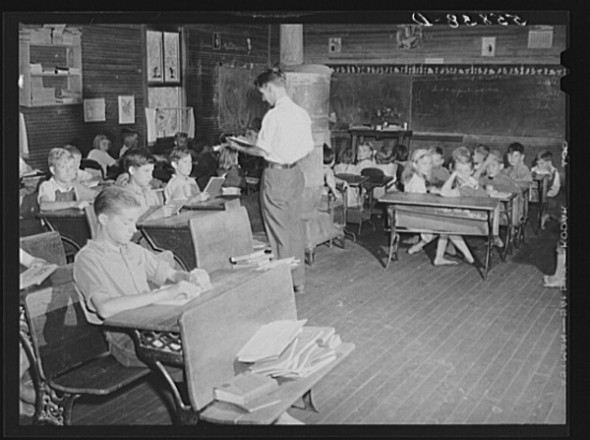

According to Wikipedia, one-room schools were once commonplace throughout rural portions of various countries, including Prussia, Norway, Sweden, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Spain.

In these rural and small town schools (some of which literally used someone's house), all of the students met in a single room. A single teacher taught academic basics to different aged children at different levels of elementary-age boys and girls.

I imagine that younger kids were hearing some of the older kids' lessons and older kids could get some remedial lessons when the younger kids were being taught. I think that could be an interesting model of learning. I also think it would be a challenging teaching assignment. It's a topic I delve into a bit deeper on my other blog.

Any debate about whether to group students by age or ability is hardly a new one. Terms like "performance-based" "ability grouping," "competency-based education" and "age-based instruction" pop up in lots of article, papers and dissertations. Classes and schools have been created around these ideas. And they still are being created - perhaps for different reasons than those that brought the one-room schools of the past into existence.

What is a school without grade levels? I read about a number of contemporary schools, including a district in North Dakota, that felt a drive to teach competencies meant eliminating age-based classrooms.

Back in 2016, I read an article in The Atlantic that asked "What If Schools Abolished Grade Levels?" Their panel concluded that sorting kids by age or ability creates problems.

What are some reasons to consider this approach to education?

In traditional classrooms, the learning is likely to be too fast or too slow for a good percentage of the students.

Rather than using "seat time" (students progressing through school based on the amount of time they sit in a chair), base promotion onward on mastery of competencies and skills.”

Allowing students to learn at their own pace, including progressing more quickly through content they truly understand.

Those sound good. Are there any potential problems with this approach?

Grouping by ability rather than age could increase social interruptions. Having taught middle school and high school, I would tell you that there are some big differences between a sixth grader (typically 11 years old) and an eighth grader (at 13). Even more dramatic would be a class with two very good math students that are 12 and 16 years old. I actually saw that happen several times when middle school students were allowed to go to the high school (or even local college) for advanced classes. I know it works on television for Doogie Howser and Young Sheldon, but maybe not so smoothly in real life. Maturity, socialization and self-esteem are all considerations.

Scheduling and assigning courses for each student becomes more complicated.

But even if you question the pedagogy of this approach, what about the andragogy? When we train adult employees or our returning adult undergraduates and graduate students, how do we group? Do we put the 45 year-old woman working on her MBA separate from the 26 year old? Of course, we do not. Through some screening or admission processes, we often put learners in groups based on ability. For example, an employee is brand new to the software so she will go in level one training whether she is 22 or 55 years old.

The old one-room schools were primarily for the lower elementary grade levels, and they very much were products of economics, supply and demand, and necessity. Perhaps, new one-room schools would also work better at those levels rather than at the high school level. We already see some of this arrangement informally or just be accident in higher education and we certainly see it in training situations. This might be the time to reexamine the formal use of ability grouping at different ages and in different situations.

Amber says in her newsletter, that looking ahead "We will also continue to see social responsibility expand beyond the consumer. For example, let's think about investment dollars into new technologies. In the US alone, according to PitchBook, venture capital investment in US companies hit $100B in 2018. If we dig into these dollars, there are very few memorable headlines about ethical investments, but that is bound to change - especially as executives at large tech companies set new standards.

Amber says in her newsletter, that looking ahead "We will also continue to see social responsibility expand beyond the consumer. For example, let's think about investment dollars into new technologies. In the US alone, according to PitchBook, venture capital investment in US companies hit $100B in 2018. If we dig into these dollars, there are very few memorable headlines about ethical investments, but that is bound to change - especially as executives at large tech companies set new standards. As the year comes to an end, you see many end-of-year summary articles and also a glut of predictions for the upcoming year. I'm not in the business of predicting what will happen in education and technology, but I do read those predictions - with several grains of salt.

As the year comes to an end, you see many end-of-year summary articles and also a glut of predictions for the upcoming year. I'm not in the business of predicting what will happen in education and technology, but I do read those predictions - with several grains of salt.  Now that Serendipity35 has passed the decade milestone, I'm finding two things happening as I write here.

Now that Serendipity35 has passed the decade milestone, I'm finding two things happening as I write here.