An Open and Shut Educational Case

Here are some concepts that I see used as hashtags, which is a sign that they have a following: lifelong learning, lifewide learning. open education, open learning, open universities. Around 2012, when MOOCs went large, the open of Massive Open Online Courses was a really important part of what defined those courses. Today, the open part has been lost in many instances where you see the MOOC term applied to an offering.

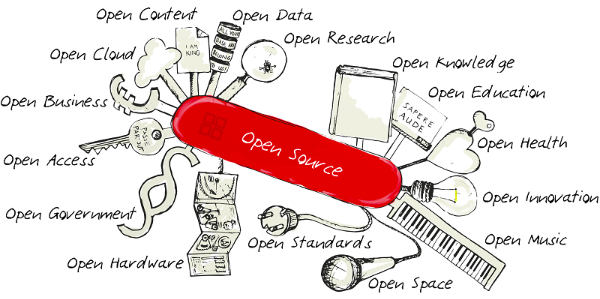

I created a category here in 2006 called "Open Everything" as an umbrella term for what I saw as a trend which would include MOOCs, OER (Open Educational Resources), open textbooks, open-source software and other things used in "open education" and beyond what we traditionally have thought of as "education," such as training, professional development and unsupervised learning.

It's not that this openness started in 2012. In 2006, I was posting in that category about a conference on interoperability, iTunes U, podcasts, Creative Commons and other open efforts. It wasn't until 2008 that I used the term "Open Everything" in a post as a movement I was seeing, rather than just my aggregated category of posts.

That 2006 conference brought together schools using different course management systems (CMS such as WebCT, Blackboard, Moodle, Sakai) to see if there might be ways to have these open and closed CMS work together. Moodle and Sakai were open-source software and schools (including NJIT where I was working) were experimenting with them while still using the paid products. At that time, a survey of officials responsible for software selection at a range of higher education institutions responded in a survey that two-thirds of them had considered or were actively considering using open source products. About 25% of institutions were implementing higher education-specific open-source software of some kind.

On a much larger scale, there were open universities with quite formal learning, such as the Open University in Great Britain. There were efforts at less formal learning online, such as Khan Academy. There was also the beginning of less formal learning from traditionally formal places, such as MIT’s OpenCourseWare.

The MOOC emerged from the availability of free resources, such as blogging sites, that were not open in that you probably could not get to the code that ran it or reproduce it elsewhere but were freely available.

The Open Everything philosophy embraces equity and inclusion and the idea that every person has a right to learn throughout their lives. It champions the democratization of knowledge.

In the 14 years since I started writing about this, we have made progress in the use of OER. Open textbooks, which I literally championed at conferences and in colleges, are much easier to get accepted by faculty than it was back then.

Unfortunately, some things that began as open - MOOCs are perhaps the best example - are now closed. They may not be fully closed. You can still enroll in courses online without cost. You may or may not be able to reuse those materials in other places or modify them for your own purposes.

In 2017, I wrote that David Wiley makes the point about "open pedagogy" that "because 'open is good' in the popular narrative, there’s apparently a temptation to characterize good educational practice as open educational practice. But that’s not what open means. As I’ve argued many times, the difference between free and open is that open is “free plus.”

Free plus what? Free plus the 5R permissions." Those five permissions are Retain, Reuse, Revise, Remix and Redistribute. Many free online resources do not embrace those five permissions.

I view the once-open doors are mostly shut. I hope they won't be locked.

Researchers expected it a year and a half ago, but Facebook is finally giving researchers access to a lot of data. The data is about how users have shared information, including misinformation, about political events around the world.

Researchers expected it a year and a half ago, but Facebook is finally giving researchers access to a lot of data. The data is about how users have shared information, including misinformation, about political events around the world.

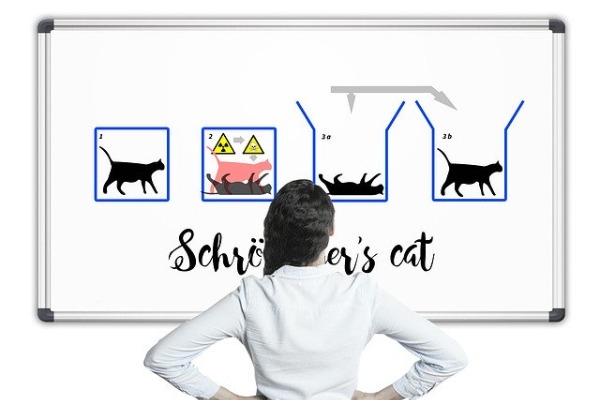

Here's a leap beyond cats and coins that came to me because I was surfing through channels on the television and saw that Christopher Nolan's film Inception.

Here's a leap beyond cats and coins that came to me because I was surfing through channels on the television and saw that Christopher Nolan's film Inception.